|

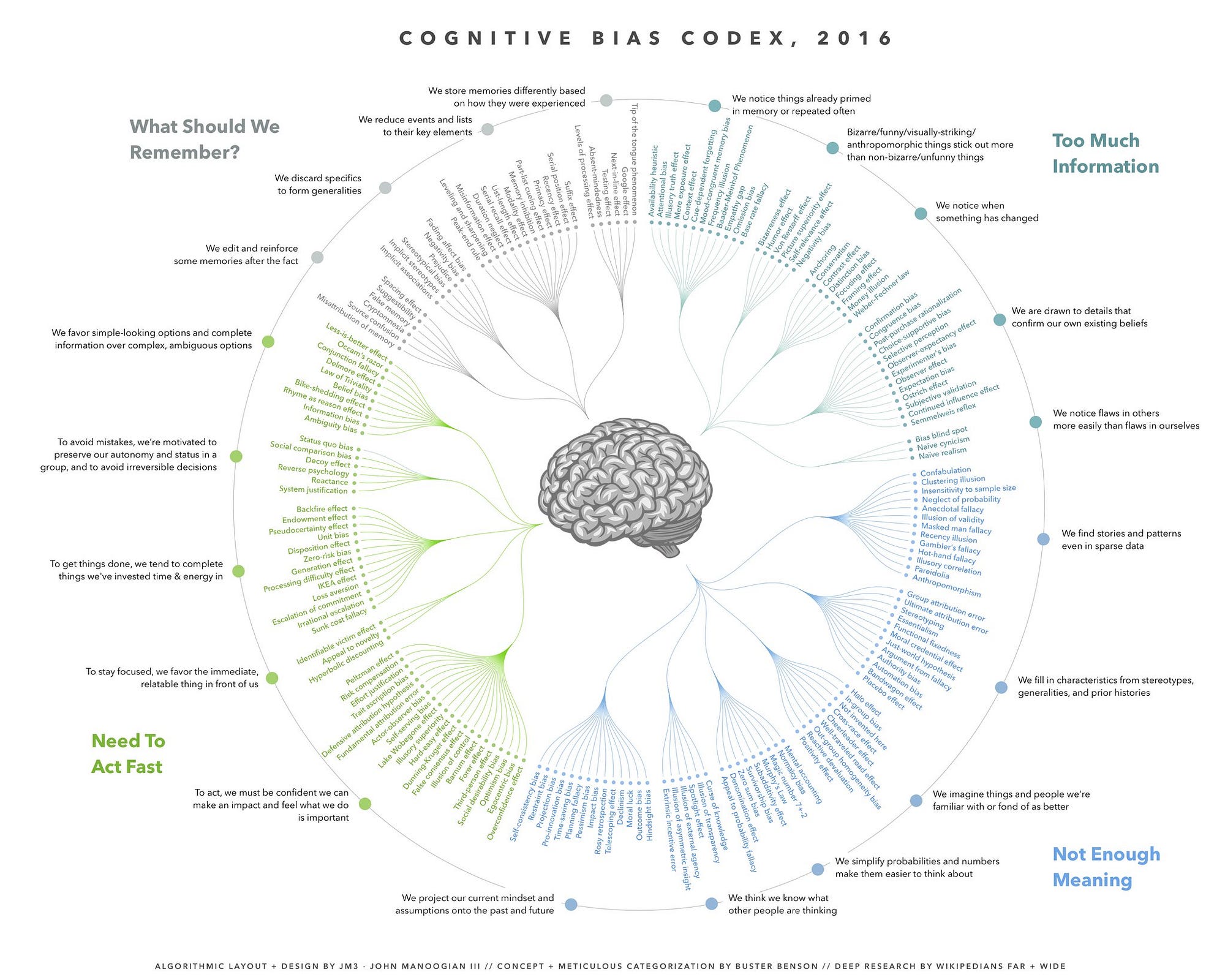

| chart by John Manoogian III |

But staying inside the framework's boundaries is far more difficult than it sounds. We've talked a lot already about some of the drivers of poor research practices. Many of us speak of corners cut due to the high stakes pressures to publish, to earn our PhD's and to acquire grant funding.

I would argue that the (probably) very common habits such as quietly trimming off outliers, or side-railing inconsistent replicates are not driven by the high stakes pressures. I'd be willing to bet they are more likely driven by the biases that might serve our artistic impulses--to mold misshapen results into an expression of our data that looks as pretty as we imagined it might look when we first set off to run the experiment.

Poor (or no) pre-planning of experiments seems to come from the lack of training, or an unwillingness to go back and relearn, or an unwillingness to take on the cost of heavy prescriptions (eg, a power analysis that says a large sample size is needed).

But I'm also beginning to give a lot of credence to the idea that the bias we introduce into our research is more subtle and pernicious. That it arises from some very primitive--and inescapable-- behavioral functions. See Dan Ariely's thoughts on the rationalization of cheating, for example.

Along comes Buster Benson, who appears to have given bias a lot of thought. He reaches the following conclusion while organizing a large compendium of cognitive biases:

"Every cognitive bias is there for a reason — primarily to save our brains time or energy."In this view, bias is an adaptation. It's a feature, not a bug, of behavioral biology. Bias is how we solve difficult problems. We have evolved all types of biases because we face all kinds of problems.

Benson isn't just some random blogger operating in a vacuum. There's some serious scholarship behind the idea (pdf). For example, that willingness to go through with a severely underpowered experiment, would be considered an "error management bias" solution for the problem of blowing the year's budget to test just one hypothesis.

Although bias might be human nature, that's not going to dismiss the biased solutions we arrive at as researchers, which are also problems themselves. One's that we'll probably have to solve with some other bias. And so on.

This is why operational frameworks come in so very handy.